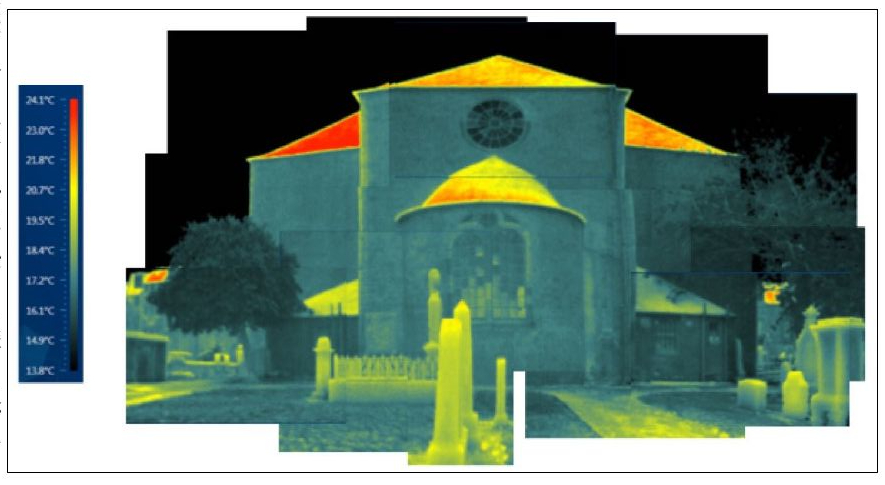

Thermal imaging is a popular idea and it certainly produces pretty pictures. One set of churches has said to us they were thinking of getting one to use on all their buildings. That can be a good thing to do, but you need to understand why. The pictures are a compelling way of changing hearts and minds, but they only provide useful technical information in limited circumstances.

Thermal imagers sense the infrared radiation coming from the surface and translate that into surface temperatures. Those temperatures are then mapped onto a set of colours from “cold” to “hot” to make it easier to for people to understand the data.

The first problem is simply that materials differ in how efficiently they emit infrared thermal radiation, so stone, metal, and glass could all be at exactly the same temperature, but they will show up as different ones to the camera. Cameras will let you set the emissivity of the material you are imaging so you get the right temperature back, but it’s the same value for the entire image. That’s fine if you point it at a uniform bit of wall, but not if you want to capture the facade of a building that has a mix of materials with very different emissivities. With care, it is possible to interpret the data technically, but it’s not as easy as point and click.

The second problem is that the angle at which the image is taken will also affect the readings. Ideally they should be taken straight on, i.e., from the same height as the subject. This can make comparing readings in two different images tricky in practice, or even interpreting one image of a complex shape. Typically the screen is at a slight angle to the actual camera, making it difficult to take images straight on. In addition readings will be affected by the distance to the subject, light sources, and even the relative humidity when the image is taken.

The third problem is just one of how the cameras tend to be used. By default, the camera will maximise the colour range in the image, so red doesn’t always mean the same thing if you take more than one image. Usually people forget to record what the colour scale actually means in each picture, and on some cameras it’s actually hard to find out. Some of them do let you set a constant colour range that won’t change between pictures, but you still have to remember to record what that was.

This doesn’t make the cameras useless. If a temperature difference is large, you will see it, and it is possible to draw reasonable conclusions from more complex images – it just takes a lot of experience to get it right. It takes less skill to do things like finding pipe runs and checking whether hidden insulation behind a uniform surface is patchy. One of the major uses takes no skill at all – convincing people to address heat loss they could find very well without the camera. It used to be important to have a thermal image as part of a grant application, because funders found them just as convincing as everyone else! We don’t know if this is still the case; from what we’ve seen these days they are likely to require a professional assessment of the building’s needs.

It’s often possible to borrow thermal imaging cameras from the local Council, the library, or a local tools library if your area has one. We have one that we can borrow for use in Edinburgh venues, for those buildings that have a specific need.

Main image: (c) Alison Hertog, from her MSc in Sustainable Energy Systems, “Hard data and meaningful analysis from thermal imaging of buildings”, 2016.