We use inexpensive DHT22 temperature and relative humidity sensors, so we don’t assume they are reliable. Instead we compare them with each other and with the most common off-the-shelf devices we see in use, Lascar EL-WIN-USB loggers. Our Lascars claim accuracy of 2.25%RH in the range 20-80% RH. Years back, we had some engineering students test that against a sling psychrometer. Our Lascars are old now and may themselves be performing worse than they were – proper engineering kit is calibrated regularly and much more expensive as a result. Our project is about conveying concepts and getting a good idea of the lay of the land, not providing professional services, so we think our more laid-back approach to checking our sensors are OK is still suitable.

To test a sensor, it’s important to check it over the range of readings you might experience in practice. If a sensor reads high or low compared to the correct value, that might not matter – if it’s consistently high or low by the same amount and you know what that amount is. That’s called a linear relationship, and you can correct for it by adding or subtracting a constant offset. The real problem is when the difference is non-linear, especially if it’s all over the place. For every sensor unit we hand out, we intend to show how it reads compared to a set of sensors including a Lascar or two. Of course, all of our sensors could be out, but the chances of that happening and them behaving similarly are pretty slim, especially if there are two different types in the set.

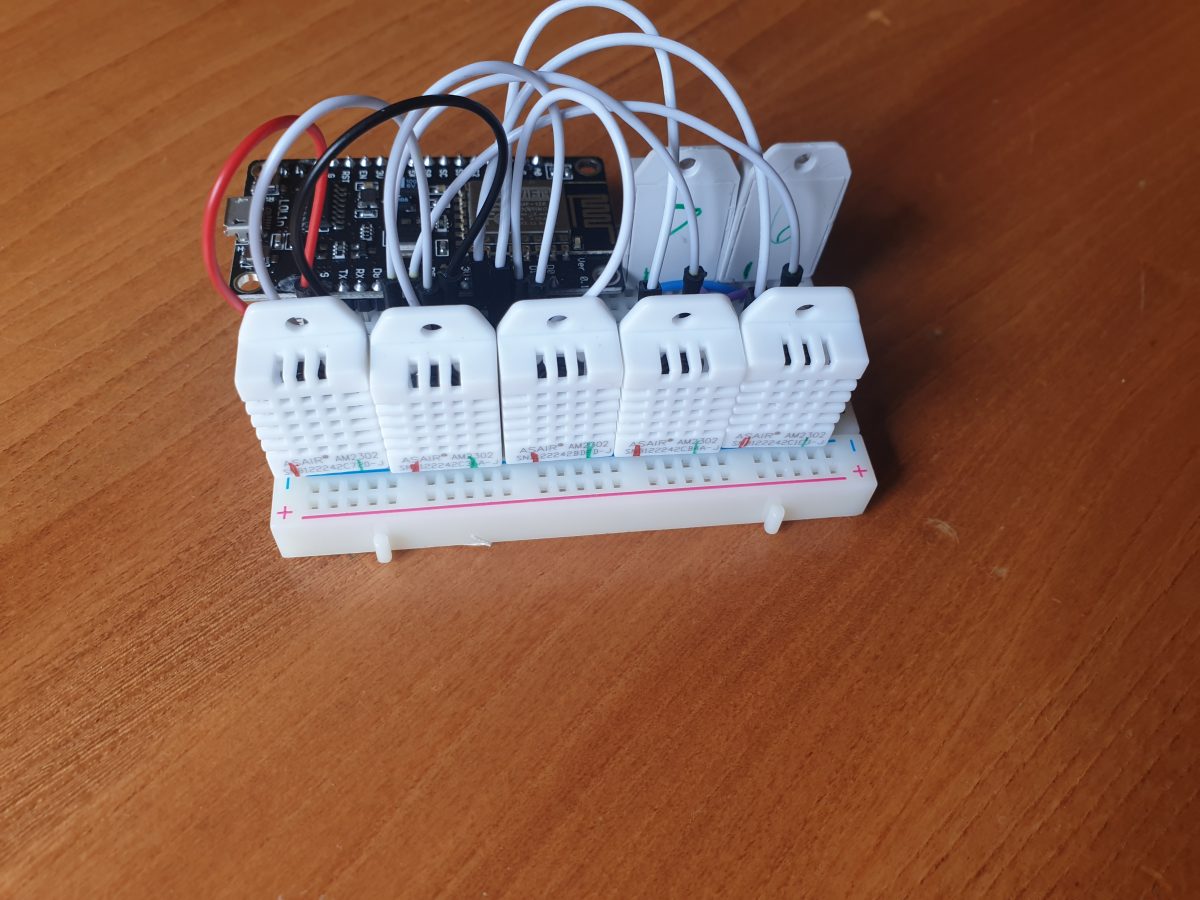

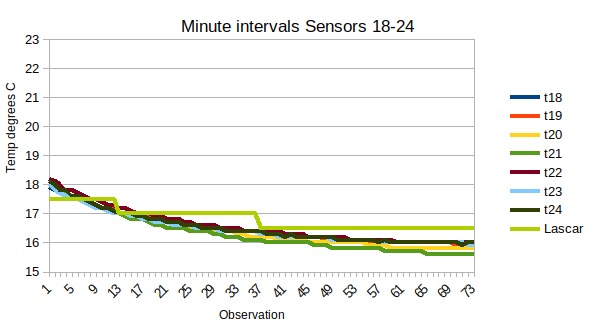

Unfortunately, it hard to do this kind of testing in the summer. Here’s what we found by putting our calibration test rig in a Scottish shed overnight.

The error for temperature is always under 1C and less than 0.5C for most of the sensors – they disappear from the graph because they’re all on top of each other. Of course in any situation where temperature is critical, it would be wise to check it from time to time – sensors do drift with age. In our buildings, spaces that host child care are a good example. In Scotland, if they aren’t above 16C, the children have to be sent home. That’s something community spaces really want to get right.

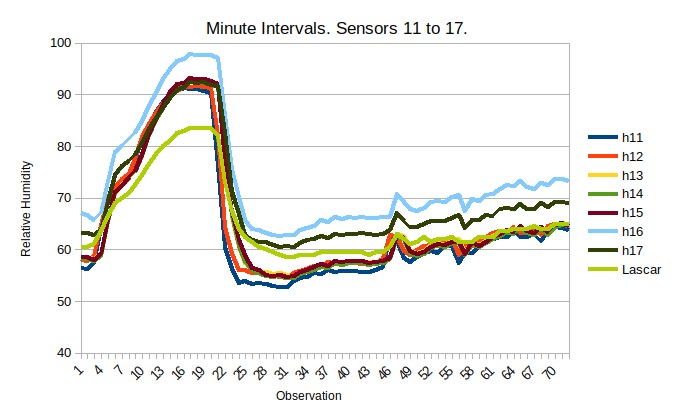

Even in summer, it’s easy to manipulate relative humidity for a calibration test – we just put the sensors in a shower room.

At first glance, the relative humidity readings don’t look very good, with the Lascar logger sometimes nearly 15% RH below the highest DHT22 reading. That’s deceptive, though – none of these sensors claim to be accurate outside 20-80% RH, and by design, Lascars respond to changes more slowly than DHT22s. In the correct range and after allowing for slow response, there is fair consistency, and under 10% error. This isn’t as good as the claim on the data sheet, but it’s good enough to be useful. The sensors vary in how fast they respond to quick changes, but that’s not very important for this use. Two of the DHT22’s are unbadged versions which we thought we’d try as they are cheaper. You might guess the top blue line is one of these but you can’t spot the other one.